Few California school districts have tested water for lead, even though it’s free–

Jill Tucker

Aug 13, 2018

As students head back to class across California this month, many will sip water from school fountains or faucets that could contain high levels of lead.

That’s because two-thirds of the state’s 1,026 school districts have not taken advantage of a free state testing program to determine whether the toxic metal is coming out of the taps and, if so, whether it exceeds federal standards. Among the 330 districts that have started or completed testing, one in five identified at least one school where levels exceeded the federal standard, according to data submitted to the state by June 1.

The testing by local water utilities has been available to every public and private school in the state for more than 18 months. Exposure to high levels of lead can cause irreversible neurological and brain damage, including lowering a child’s IQ.

That testing identified 158 samples from school fountains or faucets with high lead levels, and while that is fraction of the 14,000 tested so far, some had lead at levels far exceeding the federal guidelines of 15 parts per billion, according to the California Water Resources Control Board, which oversees the program.

A water faucet in a storage room at a Daly City’s Tobias Elementary School tested at 1,900 parts per billion — 127 times the federal standard — although the faucet was inaccessible to students, district officials said.

A water fountain in the gym at San Francisco International High School on Potrero Hill tested at 860 parts per billion.

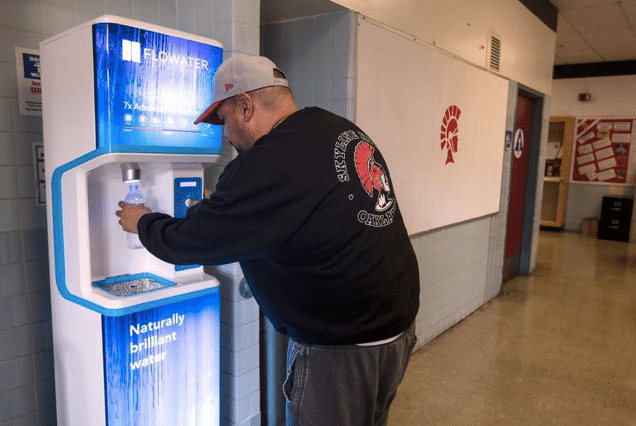

Oakland Unified decided to do independent initial testing of its 87 school last August and found seven taps with lead above federal standards, including one at the Glenview Elementary temporary campus at 60 parts per billion. Subsequent testing by East Bay Municipal Utility District has found no taps above 15 parts per billion. In May, district officials decided to install water stations at 110 schools using funds from the city’s soda tax.

At Oakland’s Conservatory of Instrumental Vocal Arts High School, a charter school located at Merritt Community College, testing identified five taps with high levels of lead, including a drinking fountain in the men’s locker room that tested at 90 parts per billion.

An additional 555 school taps across the state had lead levels of 5 to 15 parts per billion, which the health and consumer activists say is still too high. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that water lead concentrations in school fountains not exceed 1 part per billion, while other experts say less than 5 is more realistic.

All taps found with high levels of lead were removed from service or had repairs made.

Under the state voluntary program that began in January 2017, districts can request the free testing from their local water utility, which is then required to test within 90 days, collecting samples while school is in session and from at least five taps at each site.

Given the results of testing so far, it’s safe to assume that many more schools have lead coming out of the taps children will be using when they return to school, some as early as this week, said Laura Deehan, public health advocate for CalPIRG, a consumer rights group.

“The fact that kids are going back to school, that is unacceptable,” she said. “I urge all schools to get their drinking water tested right away and take action wherever they find lead.”

The voluntary testing program expires Nov. 1, but all districts will eventually see testing at all their school sites.

In October, the governor signed legislation requiring local water utilities to sample taps for lead in all state public schools by July 2019. The measure puts the onus on the water providers, rather than school districts, to initiate testing.

In the meantime, Pleasanton Unified is among the 600 districts that have yet to sample school taps for lead.

“We had planned to start last year, but things just got delayed,” said district spokesman Patrick Gannon, citing scheduling conflicts. “The tests have to be done during the school year, so we had to wait until the fall.”

In April 2017, San Francisco Unified was among the first districts to start testing for lead, finding in initial results high lead levels in the water at three schools: West Portal and Malcolm X elementary schools and San Francisco International High School. Malcolm X Elementary is in the Bayview.

The district took the fountains and faucets out of service and subsequently tested all taps at those schools.

Berkeley Unified tested most of its schools in December, finding three taps with lead above the federal standard, including a theater lobby fountain that had been inaccessible because of construction work. It tested at 640 parts per billion, a result probably caused by stagnant water sitting in the pipes for months, officials said.

Based on the results, Berkeley Superintendent Donald Evans took a strict stand on lead, adopting a new district policy that restricts lead content in water to below 1 part per billion.

Castro Valley, Dublin, Fremont and New Haven school districts were among those statewide that, as of June 1, had not submitted any results to the California State Water Board.

Some districts tested late in the school year but had not yet submitted results by June 1. Other districts, including Fresno, started testing within the last two months at sites where summer school was in session. Dublin officials said they tested a sampling of taps last year but used an outside contractor to do the work. Additional testing will be done by the local water utility during the upcoming school year, with those results submitted to the state.

Still, with thousands of schools left to test statewide, Flint said that there appears to be confusion about how the voluntary program works and who pays for it, despite outreach by children’s health organizations, environmental groups and the California School Boards Association.

A “fair number of districts” are not fully aware of the free program or don’t understand how easy it is to implement, Flint added.

Concerns about the presence of lead in water have been prompted at least in part by the water crisis in Flint, Mich., where corrosion of pipes led to leaching of lead into the city water supply.

Over the past two decades, lead exposure in children has been dramatically reduced because of the phaseout of leaded gasoline and lead-based paint, as well as bans on lead in food containers and other consumer items.

In 2000, about 2 percent of children ages 1 to 5 had high levels of lead, down from 88 percent in 1980, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Lead, however, is still present in many homes and schools.

Water utilities regularly test for contaminants, so in California, the water flowing into schools is safe, officials say. But lead in fixtures and pipe solders installed before 2010 can leach into the water.

While sampling taps isn’t error-free or comprehensive enough to ensure an absence of lead at a school, it’s still worthwhile, said Marc Edwards, Virginia Tech professor of civil engineering and an expert in lead and water.

Edwards said he isn’t surprised many California districts didn’t take advantage of the voluntary testing program, despite it being free.

“Most things that are voluntary at schools just don’t get done because schools have so many mandatory things to do,” he said.

A previous version of this story misstated the share of districts that tested and found elevated levels of lead in at least one school. It is 20 percent. The story has been altered to reflect this change.

Read the original article here